Cosmin Koszor-Codrea published the article “The Politics of Bacteriology: Epidemics, Medicine and Scientific Racism in Romania, 1880–1914” in the May 2025 issue of the academic journal “East Central Europe”. This article examines the scientific contributions of Romanian medical elites to the struggle against some of the deadliest epidemic diseases prevalent around the turn of the twentieth century. It begins by analyzing the participation of Romania in international sanitary conferences and the important role it played in shaping regional political, scientific and racial narratives employed on the ground to halt the spread of cholera, plague, and yellow fever. The article further discusses some of the key moments in the development of bacteriology in Romania and the subsequent understanding of the interrelationship between the management of human and non-human microbes, tracing the political and social consequences of laboratory science. Finally, the article examines how bacteriology became the central solution to the spread of epidemic diseases and came to hold a central place in racial narratives that targeted vulnerable ethnic and social groups in Romania and beyond.

Author: daquas_nec

Proaspăt tipărit

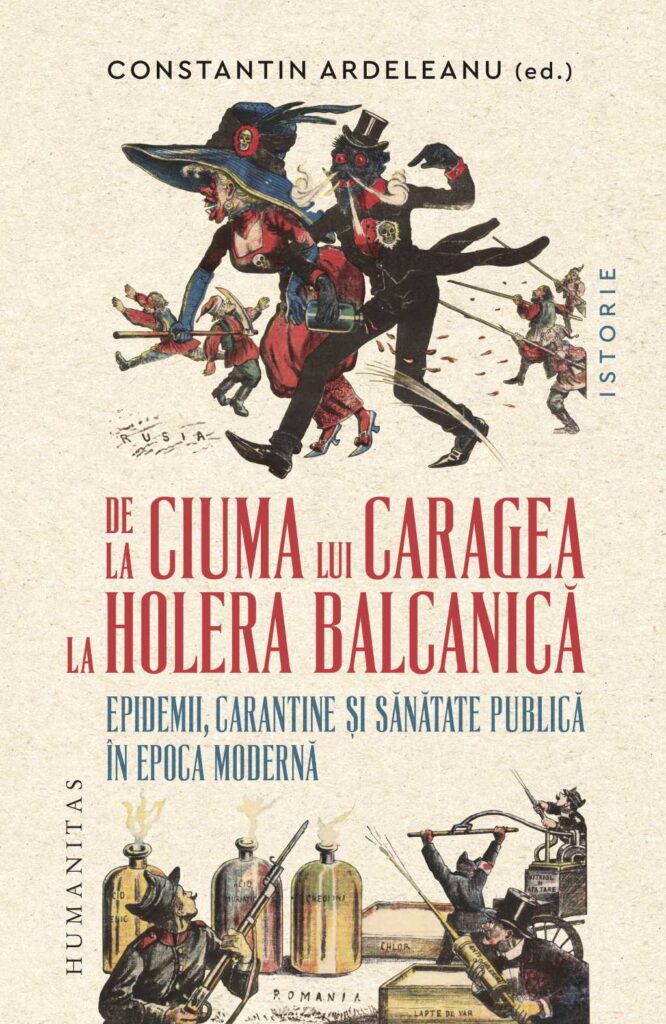

A apărut la editura Humanitas volumul De la ciuma lui Caragea la holera balcanică. Epidemii, carantine și sănătate publică în epoca modernă. Detalii sunt disponibile aici.

Interviu despre proiectul DaQuaS

Newsletter-ul Society for Romanian Studies (2024/toamnă-iarnă) include un interviu cu Constantin Ardeleanu. Tema discuției privește proiectul DaQuaS. Interviul a fost realizat de Anna Batzeli.

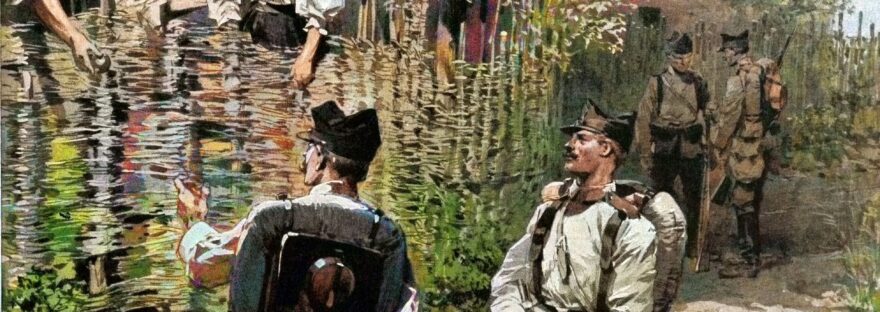

Dușmanul universal, 1911

„Dușmanul universal: O spaimă cu care se luptă lumea întreagă. Izolarea unui sat ai cărui locuitori cred că medicii îi otrăvesc pe cei suspectați de holeră. Un sătuc infectat înconjurat de soldați. Pare aproape de prisos să spunem că în întreaga lume se duce o mare luptă împotriva acestei boli de temut – holera; chiar în aceste momente se observă că vizita regelui și a reginei în Malta, în drumul lor spre India, a fost anulată din cauza unei epidemii de holeră care bântuie acolo. Poate că cea mai remarcabilă fază a acestei vizite a molimei vine din România și oferă o paralelă cu o demonstrație recentă din Italia, unde țăranii ignoranți, crezând că medicii au dus bolnavii de holeră la spital pentru a-i ucide, au luat cu forța “cazurile” de la autorități și i-au dus pe muribunzi pe umeri până la casele lor. Desenul nostru este preluat dintr-o schiță făcută în România. Corespondentul de acolo ne spune: ‘Țăranii, crezând că medicii otrăvesc orice ‘suspect’ dus la spitale, își ascund bolnavii, iar în unele cazuri atacă și înving autoritățile care fac inspecția. Când această acțiune se desfășoară într-un sat, guvernul îl izolează, înconjurându-l cu soldați. Femeile din sat arată un interes considerabil față de militari.'”

Illustrated London News, 1911

Patrulă pe frontiera româno-rusă, 1905

„Eforturile României de a împiedica pătrunderea holerei pe teritoriul său. O patrulă de frontieră formată din pușcași respinge călătorii care încercau să treacă frontiera rusă peste Prut.

Precauții împotriva holerei în România. Eforturile României pentru a preveni pătrunderea holerei pe teritoriul său. Rapoartele privind prezența holerei în anumite părți ale Rusiei au stârnit temerile autorităților române, care au luat măsuri ample de precauție pentru a împiedica intrarea molimei în țara lor. Gărzile de frontieră și pușcașii au fost staționați de-a lungul întregii frontiere și au datoria de a se asigura că călătorii din Rusia intră în România doar prin una sau două stații unde pot fi supuși unui examen medical strict și supravegherii medicale de cinci zile.”

Illustrated London News, 1905

Romania’s Sanitary Law (1874)

On 19 April 2024, Lidia Trăușan-Matu presented the paper ‘Preventing Cholera. The Sanitary Law of 1874 and the Evolution of the Quarantine System in Romania (1874–1913)’ at the international conference Toward Cholera Epidemics Elimination: From Past to Contemporary Societies, organised by the Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan & Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf. The presentation was given online and was written together with Prof. Octavian Buda.

“In this presentation, we propose to discuss a very current topic: the issue of epidemics, quarantine and health policies, but in the 1875-1913 period, in Romania. Why should we be concerned with such a subject? Because the disasters produced by epidemics, regardless of their type, place and time have profound and long-term social, political, economic and cultural effects and they reveal the problems of each country’s governance, economy and health systems. Being aware of past experiences can help us form a better, more accurate understanding and perspective of the sufferings and imbalances recently caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

This presentation aims to analyse how the sanitary law of 1874 consolidated and prioritised the public sanitation and hygiene measures in Romania to the detriment of the authoritarian rules of quarantine and compares these changes and events with the international situation, particularly in South-Eastern Europe. In the first section of the presentation, we will discuss the principles enunciated by the 1874 law regarding the prevention of contagious diseases. The second part analyses the state’s intervention solutions in the case of cholera epidemics: from the appointment of district and city primary physicians to caretake epidemics to the replacement of land quarantines with sanitary inspection and disinfection stations; from the establishment of temporary isolation hospitals to the creation of cleaning and sanitation plans for villages and towns or home improvement plans. The last part of the presentation highlights the state’s contribution in the fight against epidemics and summarises the practical lessons learned from the management of past epidemics.”

Presentation by Cosmin Koszor-Codrea at the Institute for Romance Studies, Jena University

On 19 March 2024, Dr. Cosmin Koszor-Codrea will give a guest lecture at Jena University. THe topic is ‘Science and the State. Darwinism, Race and Medicine in the Making of Modern Romania’.

The following presentation will give a brief overview of the intellectual roots and the development of racial scientific theories circulating in Romania during the nineteen-century. It will show the ways in which racial classification of hu- man varieties have mingled with Darwinian evolutionary theory and how these were further adopted within the teachings of natural history in the secondary schools. The discussion will also deal with the ways in which Romanian scientific ideas building on nation-state political agendas overlapped with eugenic ideas and the racialization of the local Jewish and Roma community. Finally, the presentation will discuss the relationship between quarantine polices promoted by the International Sanitary Conferences and their adoption in Romania and how these overlapped with advances in bacteriology that made use of epidemics and racial narratives discriminating the local ethnic minorities.

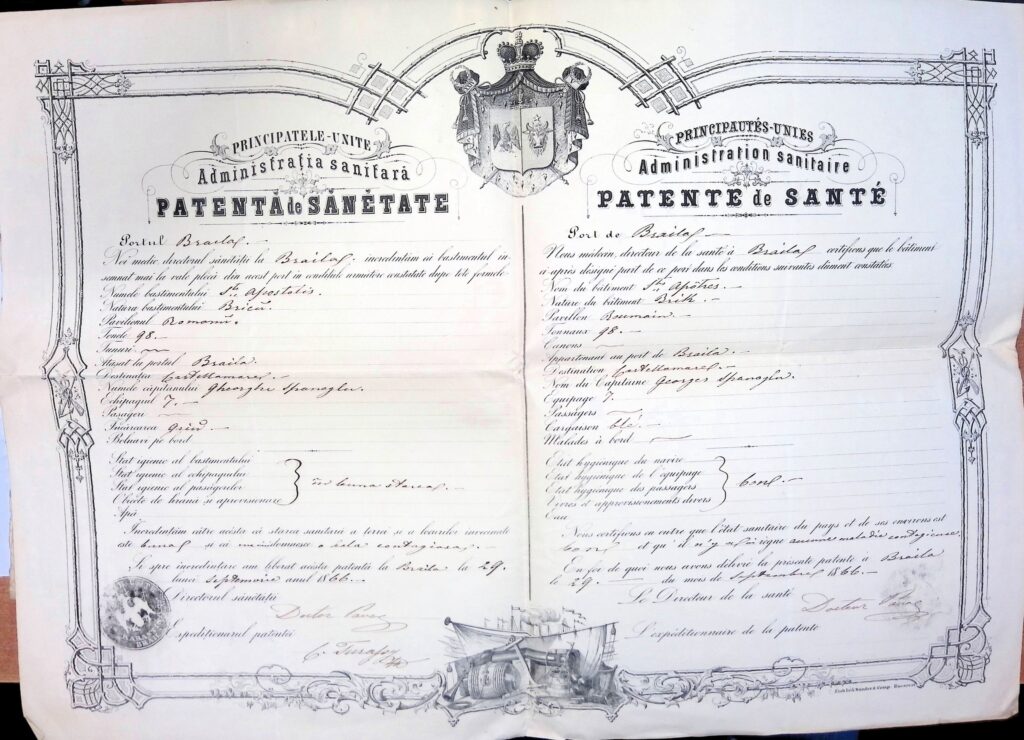

Patentă de sănătate

Model de patentă de sănătate publică, emisă de autoritățile române în anul 1866.

New presentation by Lidia Trăușan-Matu

On 14 December 2023, Lidia Trăușan-Matu will give a talk during a monthly meeting of GRIPS, a research group hosted by NEC. Lidia’s paper is entitled “Sănătate și societate. Doctorul Iuliu Barasch și sistemul carantinelor din Țara Românească între 1830 și 1863” (“Health and Society. Doctor Iuliu Barasch and the Quarantine System in Wallachia between 1830 and 1863”. Towards the end of 1829, against the backdrop of the horrors caused by the plague in Romanian society and the panic that preceded its appearance, the Russian General Pavel Kiseleff, Governor of the Principalities between 1829 and 1834, decided to implement Article 6 of the Adrianople Peace Treaty. This allowed Wallachia and Moldavia to organize quarantines and permanent sanitary corridors “along the Danube and elsewhere in the country where they may be needed” as a deterrent against plague and cholera epidemics from the East and Asia. With the help of the writings of Dr. Iuliu Barasch, a quarantine doctor in Călărași between 1843-1845, Lidia Trăușan-Matu aims to describe how the Danube quarantine system of Wallachia worked, according to what model/model it was set up and what functions it fulfilled, where the quarantines were located, what they looked like and who worked in them, what it was like to live in a quarantine for a while and what concerned the people isolated in them. In addition to the work of Iuliu Barasch, the author draws on a range of published and unpublished sources, including mortality lists, medical reports, and articles from the press of the time.

Rezultate finale concurs

Rezultatele finale ale concursurilor pentru posturile vacante în proiectul DaQuaS sunt postate aici.